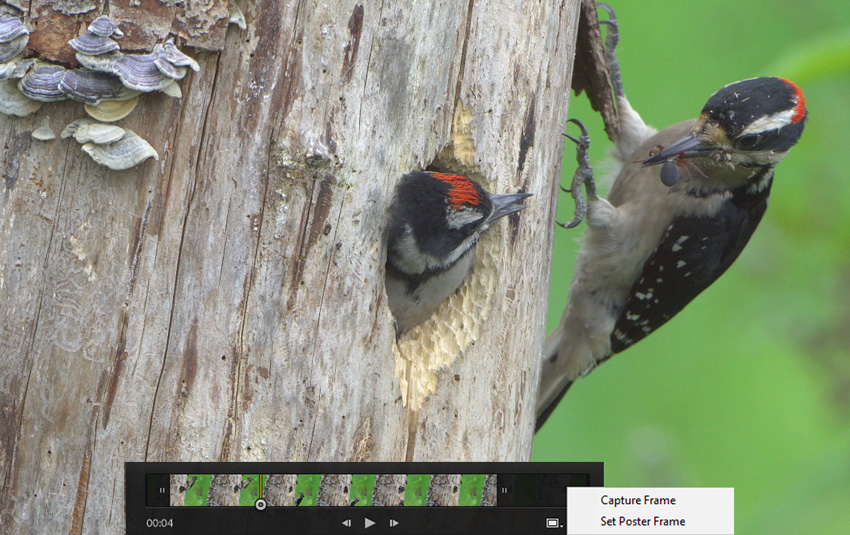

An underused advantage of shooting 4K video is in extracting serviceable stills. 4K produces good-quality 3840 x 2160 jpgs at 24 or 30 frames per second in many cameras, a faster frame-rate than the stills obtained from high-end dSLR’s or most mirrorless cameras. Some cameras can even shoot 4K at 60 f/s; the demands of slo-mo mean 120 isn’t far away. The extracted 8.3 MP image can be cropped or down-sized for the web or printed small and look outstanding, especially after a bit of post. Importantly, 4K video can be started and let run well before the anticipated action, ensuring that you won’t miss the peak.

Because the 4K images are jpgs, not RAW, lighting and correct exposure are important. Soft, even light─bright overcast if you’re shooting action─is best.

The set-up for stills from video when considering action shots like sports or wildlife requires a fast shutter speed. Video for video only use, on the other hand, demands a slower shutter that blurs action to smooth movement. To prevent blur in an extracted still, push up the ISO, but beware the cost is jerky video if your use is duel.

Some cameras allow you to set both shutter speed and aperture, with a floating ISO for correct exposure. This gives you great control, so use it if you can. Generally, I prefer setting aperture (I always want to control depth-of-field) on my Sony a6300, and then push the ISO up to get a decent shutter speed. The resultant video does indeed look jerky, but my need is often more for the stills. With ample opportunity, I vary the ISO to produce both the clean stills that I want and the best-looking video.

Some notable cameras have anticipated peak action needs and provide alternate options that achieve similar or even better results. The Olympus E-M1 II shoots electronic shutter bursts of one second at 60 fps, producing large 4:3 ratio 5K (5184×3888) RAW files. Some Panasonic cameras have a 4K Photo mode that eases the ability to extract an 8 MP image. 4K Photo further allows changing the aspect ratio from 16:9 to 3:2 or 4:3 while retaining 8 MP. It also has a loop mode that automatically deletes in camera extraneous footage after peak image capture.

You could consider extracting stills from high-definition (HD, 1080p) that creates 1920 x 1080 sized jpgs, at frame rates up to 120 or even 240. These have a use, but the quality suffers enough that even for web use a shrunk down image isn’t all that clean. Looking forward, extractions from 6K (6144×3160) and eventually 8K (7680×4320) video will be competitive with stills for many uses.

Great info Gary. Thank you for taking the time to explain this. I will experiment with video a lot more.

Great Tip! Do you use Lightroom for other video editing?

Tom, thanks for the post. Lightroom’s video tools are few. One use is to capture frame a jpg, optimizing it in Develop, and then use Sync Settings to copy the recipe to the whole video. Unfortunately, many of the Develop tools can’t be used to Sync to video. A second Lightroom video tool is cropping for export. That’s about it.

I’m using Adobe Premiere Pro for splicing together videos, editing sound, etc., but in that app I’m a total novice.