On July 10, 2020, I launched a kayak from Joseph Whidbey State Park, Whidbey Is, WA, and paddled to Smith Is. My photo target was Tufted Puffins.

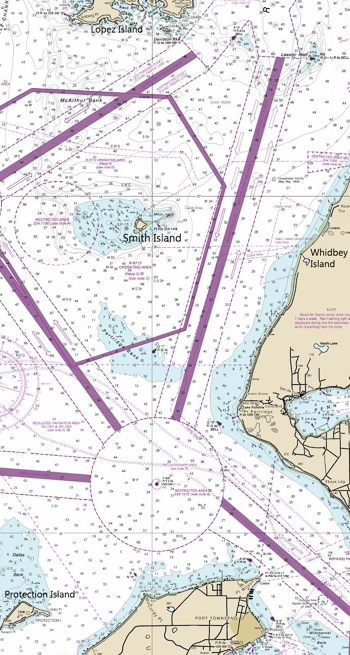

Flat-top, 400-acre Smith Island is not a destination for paddlers. The five-nautical-mile, open water route crosses a shipping lane with barge traffic and speeding watercraft. Wind from the long fetch to the west can stir a turbulent sea. Puffins hunt their prey on the open west side as well. Importantly, going ashore on Smith or neighboring Minor Island isn’t permitted. These islands are National Wildlife Refuge─so no stretch break, no potty break, no stopping for lunch. A 200 yard no entry zone surrounds their perimeter, and harbor seals, often with pups, ring the islands. Approaching marine mammals is verboten. The near offshore is a Washington State Aquatic Reserve that contains the largest bull kelp bed in the state.

Flat-top, 400-acre Smith Island is not a destination for paddlers. The five-nautical-mile, open water route crosses a shipping lane with barge traffic and speeding watercraft. Wind from the long fetch to the west can stir a turbulent sea. Puffins hunt their prey on the open west side as well. Importantly, going ashore on Smith or neighboring Minor Island isn’t permitted. These islands are National Wildlife Refuge─so no stretch break, no potty break, no stopping for lunch. A 200 yard no entry zone surrounds their perimeter, and harbor seals, often with pups, ring the islands. Approaching marine mammals is verboten. The near offshore is a Washington State Aquatic Reserve that contains the largest bull kelp bed in the state.

To stay safe, I picked a day with a light wind forecast and no fog. My kayak is closed-deck seaworthy. At the launch, I slip into a drysuit, dressing for water not air, pull on a tight-fitting spray skirt and don a PFD. I slide a spare paddle under bungie on the back deck; a chart goes on the foredeck. Stowed behind the seat are two water bottles, a pee bottle, and a small drybag with snack. My camera, a Sony A7 III with 100-400mm zoom attached, is protected in a zippered Sagebrush Dry Nose Bag. Inside as well are towel and bandana for padding and for wiping off spray. Binoculars are strapped around my neck and stuffed under the PFD. I also frequently practice self-rescue skills, and have a reliable Eskimo roll.

From Whidbey, the flat prominence of Smith Island looms a long way off. My watch reads 7:04 am. Shortly after launch, with the shipping lane a few minutes off, I turn on my marine radio to monitor Channel 16. A VHF radio is essential to alert nearby vessels or to call for help; kayaks have a low profile─I may not be seen. After a slow warm up, I paddle briskly, about 4 knots. An hour and change later, I cross the submerged tombolo that connects Smith and neighboring Minor, with some care because harbor seals are hauled out at both places. I split the difference and the mammals don’t spook. Along the outside of the kelp bed float Pigeon Guillemots, Pelagic Cormorants and numerous gulls. A few drab Harlequin Ducks, already in molt, keep their distance. I see my first puffin at about 8:45. I survey the westside cliffs, trying to determine where puffins nest.

Historically, Washington State hosted 44 Tufted Puffin nesting colonies, mostly on the coast, but with numerous sites in the San Juan Islands. As late as 1984, the minimum estimated count was 23,300 birds at 35 sites. A 2007-2010 survey found only 19 sites and 2,900 birds. Today they nest in the Washington Salish Sea only at Smith and Protection Islands, and the Protection site is in jeopardy.

Tufted Puffins arrive at Washington State nesting areas in April after a winter out at sea. They dig nest holes, or re-use old ones, usually into turf above vertical cliffs. At Smith, I see a couple hundred old holes dug just below an eroding clifftop that probably served Rhinoceros Auklets and Pigeon Guillemots; gaps above in turf and shrubs may house puffins. I see Pigeon Guillemots at the entrance of a few holes. I don’t see any cliff-roosting auklets or puffins.

A single puffin chick hatches around July 1. The nestling is brooded a few days until it can thermoregulate, at which time both parents, by necessity, forage for fish. For photographers, timing a shoot for mid-July through mid-August is optimum, with mornings a bit better than evenings for consistent sightings (less wind, too).

I turn my gaze to open water and, startlingly, see eight puffins communing like an apparition on a quiet sea. I smile so broadly my lips crack. Time to check camera settings: ISO 1600 yields a 1/2000 shutter speed at f8 for floating birds or take-offs, lens set 3m-∞ to avoid hunting. The control dial is set to Manual; I don’t want exposure changing with the background. And with WYSIWYG mirrorless, exposure feedback is visual in the viewfinder i.e. no worries. Focus is set on center point medium (Sony); in my Canon days I’d probably use center or center expanded.

I get my first shot, a puffin motoring away from me (not good), about 9 am. With binoculars, I discover a flock of gulls, along with a couple cormorants and puffins, converged at a possible bait ball, quite a bit west of the kelp bed. I paddle out and park nearby, not close, but I’m rewarded with landing shots when a puffin flies over my shoulder, banks and belly flops onto the water. I’m a bit far from the gathering, but reluctant to approach closer.

I paddle back to the kelp bed, and along the way score my best puffin portrait. I decide to park part way into the kelp, facing west with a bright morning sky behind, and hope that a puffin flies my way. Puffins are inelegant fliers. With a heavy load on short wings, they fly fast, with rapid wingbeats. Turns are long radius arcs that are easy to track until they zoom close.

Kelp beds are kayaker’s friend─they cut down waves and aid stability. A short way into the bed the water feels dead flat. I open up to f5.6 so I can shoot at 1/4000s. Very important, I pre-focus to about 60 ft. I use the kelp to focus. I don’t want a small bird in frame. I wait.

Suddenly, I pick up a puffin─OMG─flying right at me. When I look through the lens, it’s an out-of-focus blob. But flying right at me! I don’t wait, hit the focus and shoot. I get sharp shots of a tiny, distant bird. I let up on the trigger, try to re-focus, but the puffin rockets by. I just blew my best flight-shot chance. Later I get another, not-as-good look. This time I hold off, and when the puffin banks toward me, I press the shutter, stay on the bird and get a dozen sharp shots. Lip-crackers.

The sun by now is burning through clouds, the light getting harsh. A six-mile return to launch, an hour and half or so, will put me at the car at 1pm. I reluctantly pack the camera away and slow crawl out of the kelp. I re-cross the tombolo at a lower tide; there are breaking waves. Barges and watercraft are easy to negotiate in the shipping lane, but the last mile approaching Whidbey feels endless. Despite the lengthy crossing, the missed shots and six hours straight seated in a kayak, I arrive at the put-in dazed with joy.

Much of the above information about the Tufted Puffins comes from personal observations from coastal paddling in Alaska, Washington State and British Columbia. The Washington State Status Report for the Tufted Puffin, January 2015, Thor Hanson and Gary J. Wiles provided natural history background.

Great blog and great photos! Sad that the Washington puffin population is declining and the only sites left in the Salish Sea are the Protection and Smith Islands.

Thanks, Margaret. The problem with the decline is it’s just so many factors: warming sea temperatures, bi-catch from commercial fishing, declining prey, bald eagles everywhere, oil spills. Smith Island itself is eroding, too. We can be thankful there are several million up north. And I read they are increasing in the Aluetian chain.

Great adventure and photos as usual.

Thanks for sharing.

Dan

Thanks, Dan. An adventure indeed. I miss the coast, though. With the Neah Bay and La Push closed, hard to find a launch there.

Gary, this is just an extraordinary account with gorgeous shots! Thank you for providing all the background detail—ecology, avian behaviors, marine challenges, camera settings, and your own emotional responses. Add some exceptional shots and it’s a wonderful blog piece.

Thanks, Marc. It was a great day out there. Maybe not doable in your Poke boat!

Hi Gary,

Enjoyed reading your encounter with the puffins. I can imagine the challenges that are presented in such a situation. Glad you came away with some great shots of the bird.

Thanks, Robert!

This is great. I love the way you write, Gary!

Wow! I love your photos, Gary. The narrative kept me breathless to know what happens next?!

I’m so happy for your good fortune with the weather and puffins showing up.

Thanks, Diana. I picked a good day, but otherwise, a routine kayak adventure with an notable target.

I read this with rapt attention. I love how you describe every detail of the planning of your safe crossing to the best locations to photograph the birds. A thrilling read, and great shots!!

Nancy, thanks so much for your kind words. I will say that preparation becomes routine after much paddling on the coast. Writing about it, that’s another story. That took work!

Great photos! Great information!